It is easy to forgot sometimes that reading visual evidence is tricky. For the newcomer, the many possible interpretations available can on one hand seen overwhelming, on the other constrained by more obviously descriptive textual evidence. Peter Burke’s Eyewitnessing remains a canonical text for thinking through these problems (and indeed for reminding us that all evidence, not least textual, is always read only through a thick layer of human interpretation) and is a text I regularly recommend to colleagues and students alike. What Burke doesn’t address is how finding aids and metadata can make the situation worse. This may seem a curious claim. After all, finding aids combined with digital collections have made an unprecedented volume and range of visual material available to scholars and the public alike. But rarely do these finding aims search the visual evidence itself, rather they search text about visual evidence (less often text within visual evidence, even less often rich curatorial tagging such found on the British Cartoon Archive website). This yokes – if we are not careful – our study visual evidence to text and denies our ability of studying visual evidence for itself.

In an short essay I am writing for the Punch Historical Archive entitled ‘Working with Visual Evidence – ‘Reading’ Punch Cartoons’ I approach these issues of reading images discovered by textual finding aids. Punch is ideal for this purpose, because the innovative use made by Punch of text and image side-by-side (that is, for a publication intended for mass circulation) makes the cartoons therein both discoverable and hard to see beyond the voluminous text that surrounded them.

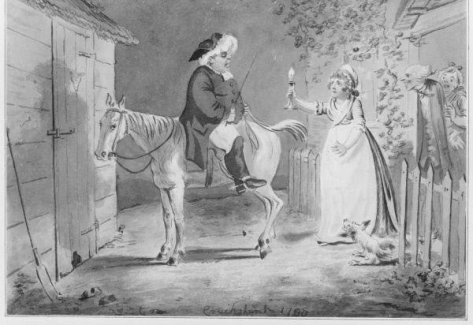

As a means of showing how themes could transcend text, the essay will contain a short study of mid-Victorian Punch cartoons that addressed the relationship between town and country. This theme has a long heritage. Indeed one of my favourite designs on the subject is Good Joke: A Groggy Parson is by the late-Georgian artist-engraver Isaac Cruikshank.

In this print a parson, his sense of orientation severely diminished, has returned from town drunk, a victim of his fellow drinkers who ‘resolved to play him a trick which was Accomplished by Mounting him with his face to the Horses Tail’. In his stupor and confusion he proclaims to his concerned wife that ‘Nothing grieves me but that the Plaguy Rogues should have cut my Horses Head off’. The comedy here is simple, playing on the impossibility of a headless horse taking a man home and that fact having escaped the groggy parson. But place also plays a central role in how the print might have been read and in turn the potential reach of the design. In short, there is nothing to suggest what or where ‘town’ and ‘country’ are. Georgian Londoners might have, for example, read the distinction between ‘town’ and ‘country’ as relating to little more than exiting ‘town’ at London Bridge and heading south into the ‘country’, or else to Hampstead Heath or Greenwich Park. And yet for a provincial audience, the same narrative of ‘town’ and ‘country’ could have been unproblematically reapplied to their local surroundings, to any two known places delimited by being or not being comparatively urban or rural. In short, the sense of place was malleable and fluid, and the humour read through the experiences of the reader as much as the direction of artist. Indeed I would suggest the intentions of the artist-engraver – informed by the needs of his publisher Laurie & Whittle (though not impressions survive, only the original watercolour) – were quite deliberate in leaving the design open to interpretation in this way.

Of course Georgian parsons are out of scope for an essay on Punch, a publication that – not unproblematically (see Henry Miller, ‘The Problem with Punch‘) – has come to encapsulate Victorian humour. And speaking of publication, the essay won’t be available under an Creative Commons Licence or similar (sorry!), but it will be freely available without the need to handover any personal details or pay a subscription thanks to the nice people at the Punch Historical Archive – indeed all existing essays in the series are available freely (Punch Historical Archive essays). I’ve been playing around with *Punch Historical Archive* for the last week and it is clear that Cengage Learning have made efforts to fit the interface to the publication. This makes for a pretty good user experience (the usual timeout issues aside), one that importantly provides a good sense of scale, both between images and between image and text, and one that doesn’t privilege text – for though, of course, text search is the primary finding aid, options for browsing make something more than smash and grab research eminently possible. Punch Historical Archive is a subscription service and it isn’t for me to say whether you or your library will benefit from the investment (there are, of course, bits of of *Punch* scattered around the web – Internet Archive, Project Gutenberg, Wikimedia Commons). Either way the essays on Punch, including mine in the new year, will be available as a resource you can draw on and hopefully make good use of.

You must be logged in to post a comment.